Navigating Europe in 2019

Themes and Risks Investors in Europe to Consider in 2019

We are nearly 20 years into the new millennium and it is an unrecognizable place compared to when it started. Lehman is gone, Bear Stearns – gone, Merrill Lynch – acquired, Citigroup is a fraction of its former self. Blockbuster, Toys R Us, Woolworths are all part of the history books now. Europe, where we focus our attention, is in the midst of a volatile redefinition and the pace of change poses a number of challenges for investors. In the following note, we highlight a few European investment themes and risks to follow in 2019:

Political Surprises Have Recently Upended the Status Quo in Nearly Every Major Western European Country. Price in the Unexpected.

Tunisian Mohamed Bouazizi’s self-immolation in 2010 set off a chain of events that culminated in the 2011 Arab Spring and subsequently, the Syrian War. By 2015, the number of migrants fleeing into Europe had increased to over 1 million people annually.

The blowback has been undeniable. Anti-immigration, right-wing and extremist political parties have taken over in Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia, or are part of a ruling coalition in Austria and Italy. These parties now hold influential positions in the Czech Republic, Denmark, and Finland and are making headway in some of the EU’s founding members such as Germany and France.

Political risk is often an afterthought in asset valuations but in 2019, it is worth diving more into some of Europe’s political makeup:

France: (2019 Stats: +1.7% YoY Growth, 99% Debt / GDP, -2.8% Budget Deficit / GDP): Left: La France Insoumise (Jean-Luc Mélenchon), Center Left: Parti Socialiste (Olivier Faure), Center: La République en Marche or “LREM” (Emmanuel Macron – President), Center Right: Les Républicans (Laurent Wauquiez), Far Right: National Rally or “RN” (f.k.a. National Front) (Marie le Pen).

Why it matters: In the run-up to Macron’s 2017 election, the benchmark CAC-40 rose ~10%, marking a bull run that France hadn’t enjoyed since the ‘07/’08 financial crisis. However, Macron’s supply-side cuts to taxes and public services have angered voters. The resulting yellow jacket riots in recent months give Right and Left-wing parties the opportunity to gain seats at the May 2019 European Parliamentary Elections. Victories for either extreme is concerning as France moves closer to general elections in 2022.

Marie le Pen has walked back the “Frexit” rhetoric of her last run at the presidency but remains a Eurosceptic at heart and is eager to capitalize on Macron’s recent missteps. This may push the Left and the Right to run campaigns that are less pro-business than that of LREM thus adding to headwinds in an already choppy market.

Germany (2019 Stats: +1.8% YoY Growth, 56% Debt / GDP, 1.2% Budget Surplus / GDP): Left: Left Party (Katja Kipping), Center Left: Social Democratic Party or “SPD” (Andrea Nahles), Center Right: Christian Democratic Party or “CDU” (Angela Merkel – Federal Chancellor until 2021. Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer elected CDU leader in Dec. 2018), Christian Social Union (Markus Söder) or “CSU”, Free Democratic Party or “FDP” (Christian Linder), Far Right: AfD (Jörg Meuthen / Alexander Gauland).

Why it matters: Germany, the EU’s de facto leader, is changing its guard. Angela Merkel, who has led the country since 2005 and is the longest-serving G7 leader, announced plans to step down as Federal Chancellor in 2021.

The CDU party’s spat with its sister party CSU was no longer sustainable. Indeed, it was her decision to allow ~1MM refugees into Germany coupled with the rising populist sentiment on the continent that cost Merkel her long-standing coalition.

CDU/CSU losses to the Greens on the Left and AfD on the Right in Hesse and Bavaria cemented Merkel’s fate and opened the way for Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, or “AKK”, to become the new CDU leader.

With the DAX off nearly 18% from its 2017 highs, a bigger question looming is how new German leaders will confront slowing German industrial output in the face of ongoing US trade disputes, potential sanctions, and disorderly Brexit negotiations.

Greece (2019 Stats: +2.0% YoY Growth, 175% Debt / GDP, 0.6% Budget Surplus / GDP ): Far Left: Syriza (Alexis Tsipras – PM), Center Left: PASOK (Fofi Genamata), Center Right: New Democracy or “ND” (Kyriakos Mitsotakis), Far Right: Independent Greeks (Panos Kammenos), Neo-Nazi: Golden Dawn (Nikolaos Michaloliakos)

Why it matters: Greece lost a staggering 25% of its GDP between 2007 and 2016 but is slowly turning the corner. The Syriza party reversed course from its pre-crisis populist agenda and ultimately submitted to the Troika’s (IMF, ECB, and EC) demands on austerity and reforms.

Greece is now starting to deliver cautiously positive news. It successfully exited post-bailout supervision and grew GDP by 2% in 2018. Unemployment, which peaked at ~30% in 2013, is finally trending below the 20% mark.

Despite these successes, Syriza is struggling. Greece holds parliamentary elections in October 2019 but it is unclear if the unstable Syriza / Independent Greeks minority coalition will last that long (Tsipras narrowly survived a no-confidence parliamentary vote this January). There are early indications that Mitsotakis leads in the polls and could become Greece’s next PM.

With a failed populist agenda ending, a positive fiscal turnaround, a successful capital markets re-entry and a free-market leading ND party in pole position to win October elections, Greece may be the country to track this year.

Republic of Ireland (2019 Stats: +4.5% YoY Growth, 61% Debt / GDP, -0.1% Budget Deficit / GDP): Left: Sinn Féin (Mary Lou McDonald since Feb 2018), Center Left: Labour (Brendan Howlin), Center Right: Fine Gael (Leo Varadkar – Taoiseach), Fianna Fáil (Micheál Martin).

Why it matters: The open border shared by the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland is at the crux of the ongoing Brexit debate which if left unresolved, threatens to leave the UK crashing out of the EU without a transition deal. Taoiseach Leo Varadkar’s and the Teresa May’s insistence on maintaining a post-Brexit open border with Northern Ireland, and the resulting backstop agreement to ensure borderless continuity, has complicated discussions between the UK and EU.

Industry paints a dystopian future for the UK if the two sides can’t find a solution. The prospects of a no-deal for Ireland, which sent ~12% of €120BN in exports to the UK in 2017, are equally dire if not more. Ireland’s central bank estimates a no-deal Brexit would take 4% from Irish growth.

However, contrarians may posit that trade between the UK and Ireland is so intertwined, particularly in agriculture and dairy, that necessary measures would be put in place, one way or another, to ensure trade is not disrupted – even in a no-deal scenario. If one takes this stance and believes that the dystopia would never happen, then it could be argued that Irish equities and their benchmark Iseq 20, currently ~17% off 2018 highs, are oversold at current levels.

Italy (2019 Stats: +1.2% YoY Growth, 131% Debt / GDP, -2.0% Budget Deficit / GDP): Independent (Giuseppe Conte – PM /Head of Coalition Gov’t), Left: Democratic Party or “PD” (Matteo Orfini), Five Star Movement (Luigi di Maio – Deputy PM), Center Right: Forza Italia (Silvio Berlusconi), Fratelli d’Italia or “FdI” (Georgia Meloni), Far Right: The League (Matteo Salvini – Deputy PM).

Why it matters: Italy’s ongoing economic instability and banking sector crisis arguably pose a larger threat to the European project than does Brexit. As the EU’s 3rd largest Euro-currency member, Salvini’s previous threats towards the Union were particularly damaging.

The current left/right government coalition has shown its willingness to use this leverage, most recently, during last year’s budgetary fight with the Commission. It was only after its 5YR sovereign CDS prices surged +200% that the coalition backed down.

Now, Matteo Salvini is angling for a run at European Parliament where he believes he can change Europe from within. And despite previous promises, the government may look use taxpayers’ money to bail out certain distressed banks. With these concessions and an apparent change of tact from the coalition, we may see more examples of centrist (rather than extreme) maneuvering, potentially bringing some needed stability to the country.

Netherlands (2019 Stats: +2.4% YoY Growth, 50% Debt / GDP, 1.0% Budget Surplus / GDP ): Left: Green Left (Jesse Klaver), Socialist Party or “SP” (Lilian Marijnissen), D66 (Rob Jetten, Kajsa Ollongren Deputy PM), ChristienUnie (Gert-Jan Segers, Carola Schouten Deputy PM) Centre Left: Labour Party or “PvdA” (Lodewijk Asscher) Centre Right: Christian Democratic Appeal or “CDA” (Sybrand Buma, Hugo de Jonge Deputy PM), Party for Freedom and Democracy or “VVD” (Mark Rutte – PM), Right: Party for Freedom or “PVV” (Geert Wilders), Forum for Democracy or “FvD” (Thierry Baudet)

Why it matters: When current Prime Minister Rutte cobbled together his 4-party coalition (VDD/D66/CDA/CU) in 2017 securing his 3rd term, few expected the group to last. Recent scandals and disputes may prove Rutte’s doubters correct when mid-term elections take place in March 2019.

Rutte’s knack for coalition building benefited him well at home and abroad while the Netherlands was still a major natural gas exporter. Pre-Brexit, the country converged with the UK to counterbalance a Berlin/Paris axis within the EU. As the UK makes its way out of the EU, Rutte was forced to build the New Hanseatic League, a coalition of Northern European and Baltic states, to counter France’s march towards a more integrated EU.

Rutte’s push for continued flexibility within EU makes sense given the Netherland’s disappearing natural gas sector. The Dutch hold ~25% of the EU’s natural gas reserves and, together with the UK and Norway, were a main natural gas exporter to a wider Europe. However, continued earthquakes in the Dutch Groningen gas field forced the Minister of Economic affairs to start winding down production in 2017 targeting complete shutdown by 2030.

As a result, the €15BN of natural gas the Dutch exported in 2013 has since fallen to ~€2BN, turning the country into net natural gas importers. Without the Groningen field or the UK, the newly formed Hanseatic League becomes key for Rutte to maintain influence within the EU. However, as the Netherlands begins replacing its gas requirements with pipeline gas from Russia, some expect to see fissures within Rutte’s New Hanseatic League. If this happens, it will be to the benefit of France and its push for a cross-border banking union.

Portugal (2019 Stats: +1.8% YoY Growth, 119% Debt / GDP, -0.6% Budget Deficit / GDP): Left: Left Bloc or “BE” (Catarina Martins), Portuguese Communist Party or “PCP” (Jeronimo de Sousa), Centre Left: Socialist Party or “PS” (António Costa – PM), Centre Right: Social Democrats or “PSD” (Rui Rio), Right: People’s Party or “CDS” (Assunção Cristas).

Why it matters: The left-leaning SP/Left Bloc/Communist Party coalition which, to date, has delivered a remarkable economic turnaround for the country, may come under pressure in Portugal’s October 2019 parliamentary elections.

Portugal’s recovery stands in stark contrast to the rest of Europe as an example of a left-leaning socialist state which still holds sway with the population and is economically healthy. Unemployment is forecasted to fall from its 2012 highs of 18% to ~6% in 2019. 4 years of consecutive GDP growth and 3 years of Prime Minister Costas’ leadership have delivered Portugal’s best economic performance in a decade.

Markets appear to be rewarding Portugal for its performance; the PSI-20 which, was off 14% in 2018, has sharply rebounded posting 10% gains YTD.

Spain (2019 Stats: +2.2% YoY Growth, 96% Debt / GDP, -2.1% Budget Deficit / GDP): Left: Podemos (Pablo Iglesias), Centre Left: Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party or “PSOE” (Pedro Sanchez – PM), Centre Right: Ciudadanos (Albert Rivera), Right: People’s Party or “PP” (Pablo Casado), Extreme Right: Vox (Santiago Abascal).

Why it matters: The People’s Party and Socialist Workers’ Party have traded leadership in Spain since 1982. However, the duopoly was uprooted after anti-austerity Podemos and right-leaning Cuidadanos won seats across Spain in its last elections.

Spain will hold new regional and European parliamentary elections in May 2019. Pedro Sanchez, who just became PM in June 2018, may also call general elections in May if he is unable to pass his budget in parliament. Complicating matters is the rise of anti-immigration party Vox’s which won seats from PSOE in its traditional stronghold of Andalucia this past December. The recent events in Andalucía, now controlled by a PP/Cuidadanos/Vox right-leaning coalition, has upended traditional Spanish politics.

The party fragmentation is noteworthy because we observe similar dynamics in other western countries. Democrats and Republicans have traded leadership of America since Franklin Pierce’s presidency in the mid-19th century. PM Law premiership in 1922 kicked off an era of Conservative/Labour “back and forth” in the UK that continues today. These two-party structures seem increasingly dysfunctional as they hide dissenting sub-groups which eventually coalesce to hold their political parties hostage or break away. In this hyper-politicized environment, expect to see more “Spanish-like” fragmentation in traditionally two-party political systems.

UK (2019 Stats: +1.2% YoY Growth, 85% Debt / GDP, -1% Budget Deficit / GDP): Right: Conservative (Teresa May – PM as of this writing), Irish Democratic Unionist Party (Arlene Foster), UKIP (Gerard Batten), Centre: Liberal Democrats (Vince Cable), Centre Left: Labour (Jeremy Corbyn), Scottish National Party (Nicola Sturgeon).

Why it matters: Brexit has dominated the European public discourse since 2016 and, as the March 2019 exit deadline approaches, is arguably the key risk underlying Europe today. When the divorce commenced, the UK put forth its list of non-starters: No border on the Irish Sea, No customs union and No free movement of people, but this has proven to be easier said than done.

Teresa May, who has spent the past two years negotiating a transitional withdrawal agreement, had her EU approved deal turned down by UK parliament in January. Her proposal lost by a margin 203 votes making it the largest Commons defeat in UK political history. What comes next is anyone’s guess, but options include a Conservative party split, a 2nd Brexit referendum, a Corbyn Prime Minister, a Brexit delay, or who knows what else.

The uncertainty will persist well into 2019, but various frameworks for a post-Brexit UK/EU relationship have been floating around. Candidates include:

- No Deal: The UK leaves the EU with no working trade agreement in place by March 29. In this case, EU / UK trade relations would default to the World Trade Organization’s framework with associated mandatory tariffs on goods and services. A no-deal exit would have a detrimental impact on both the UK and EU economies, possibly decimate the Sterling and lead to inflation. It is a doomsday scenario which both sides are keen to avoid, but conversely, the key point of leverage May holds over the EU;

Or:

- Canada Option: Ex-foreign secretary Boris Johnson favors a CETA-like free trade agreement similar to the one Canada and the EU signed in 2016. It offers preferential access to the EU with less of the legislative burden that either Norway or Iceland endure in their relationships with the EU. It also frees the UK up to close deals with other countries. Certain goods would benefit from tariff-less trading but services would likely still face many hurdles. Free trade agreements usually take years to close and this option would not solve the Northern Ireland border issue;

- Turkey Option: Turkey enjoys a customs union with the EU giving it tariff-free access for goods into the Single Market only. Here, the UK would share a common tariff on goods imported from outside the customs union, would control its borders, and would terminate EU budget payments. However, it would likely face non-barrier tariffs for UK services, would still be required to follow EU standards, and would have no ability to negotiate bilateral deals with other countries;

- Norway Option: Norway forms part of a group of countries that has access to the EU’s single market and has a Free Trade Agreement with the union, but has opted not to join its customs union. This allows Norway to close trade deals with other countries. In this scenario, the UK leaves the EU and join the European Free Trade Association (“EFTA”). Joining the EFTA would give the UK full access to the European Economic Area (“EEA”) which, in turn, would give the UK access to the single market (save certain industries). The Norway option appears to be the least disruptive course of action and requires no Irish border. However, this option requires the UK to maintain payments into the EU budget and offers limited ability to restrict the free movement of EU citizens;

- Swiss Option: Switzerland opted out of the EU, but is part of the European Free Trade Agreement. In this scenario, the UK would leave the EU and enter into a Free Trade Agreement with the EU similar to that of Switzerland. Switzerland pays less per capita than Norway for access to most (but not all) of the EU’s Single Market through numerous bilateral agreements. The Swiss option offers less legislative oversight from Brussels but burdens the UK with maintaining EU equivalence without any say in how legislation is formed. It also risks barring important UK services from access into the single market. For example, the EU has not given Swiss financial services access to the Single Market. This is a key point as financial services make up ~7% of the UK’s GDP;

- Remain: Teresa May has resisted calls to hold another referendum on Brexit fearing it would open the door to more confusion and potentially endless calls for nationalistic referendums similar to those seen in Scotland or Catalonia. Labour party and other analysts contend that a second referendum would likely lead to a revised “remain” vote. The EU has suggested a number of occasions that it prefers the UK inside the union.

While all of this is going on, it is worth noting that the Republic of Ireland and the UK have yet to form a government that returns Northern Ireland to its previous joint power-sharing agreement. Jan 2019 marks two years that Northern Ireland has had no governing body. Northern Ireland, which is at the center of the Brexit debate holds local council elections in May 2019.

The European Central Bank’s Balance Sheet Unwind Will Be Messier Than Those of Its Counterparts

The political backdrop is especially crucial if one considers how vigourously senior politicians have been attacking the monetary policies of their central banks. The major central banks (save Japan) have finalized their respective quantitative easing programs ending a decade of monetary expansion. This is likely to take some steam out the US, hit aggressive asset valuations and add more volatility to the market globally.

The Fed started its $4 trillion unwinding process back in Oct. 2017 while the Bank of England intends to start winding down once rates reach 1.5% (at 75bps at the time of this writing). And as inflation creeps in, we see more discussions of rate hikes. Jerome Powell at the FED had, until this January, forecasted further hikes in 2019 while Mark Carney at the BoE (until Jan 2020) hinted that tight labor market and record UK employment could lead to potential hikes in 2019.

The QE unwind at the ECB is a much more complicated issue altogether:

- Dhragi sees headline inflation averaging just shy of the ECB’s 2% goal at 1.7% until 2020, consistent with a tightening labor market and potentially leading to an ECB rate hike in late 2019. However, Draghi will step down as ECB’s president in Oct. 2019 while Peter Praet will step down as Chief Economist this May. This brings some uncertainty to the direction and policy of the ECB next year;

- The ECB stopped its €15BN / month bond-buying program in 2018 capping its total purchase of sovereign, corporate, mortgage-backed bonds and asset-backed securities at €2.6 trillion. The next ECB president will need to navigate the task of unwinding the ECB’s current ~€5 trillion balance sheet while regional growth continues to lag;

- Germany’s Bundesbank chief, Jens Weidmann, was rumored to be in the lead for next ECB president. He is considered hawkish has spoken out against sustained low rates. In parallel, the EU will replace Jean-Claude Junker as President of the European Commission who steps down in May 2019. At the EC, Germany’s Manfred Weber (MEP and leader of EPP at European Parliament) is also a strong contender for next President;

- Germany is unlikely to push for German candidates at both the ECB and EC. Therefore talks of Weidmann’s ECB presidency have tailed off. Other ECB candidates include François Villeroy de Galhau (France, Central Bank governor, dovish), Philip Lane (Central Bank of Ireland, centrist) and Christine Lagarde (IMF).

The QE unwind in Europe and the eventual rates hikes will expose several companies grappling with weak balance sheets. Outsourcing and construction companies, for example, have struggled with poor operations and over-levered capital structures. These included Carillion, Interserve, Kier, Capita in the UK, Astaldi, Condotte, Trevi CMC Ravenna in Italy and OHL in Spain. Unless regional growth picks up, we are likely to see more challenges in this sector as the BoE and ECB adjust their monetary policies.

The Pressure for European Banking Consolidation Will Continue but Will Be Focused on Local Rather Than Cross-Border Solutions

As the ECB’s QE project winds down, excess liquidity is predicted to fall from a high of €2TR to ~€500BN leading to upward pressure on borrowing rates by 2022. That’s not soon enough for many institutions, particularly those faced with acute structural challenges like those currently faced by several banks in Italy.

With the ECB’s shifting target date for interest rates hikes, the average return on equity (“ROE”) across European banks will likely remain subdued (flat at 7.2% for Q3 2018 vs. Q3 2017). This stands in contrast to the average equity return of US institutions which today hovers around 12%.

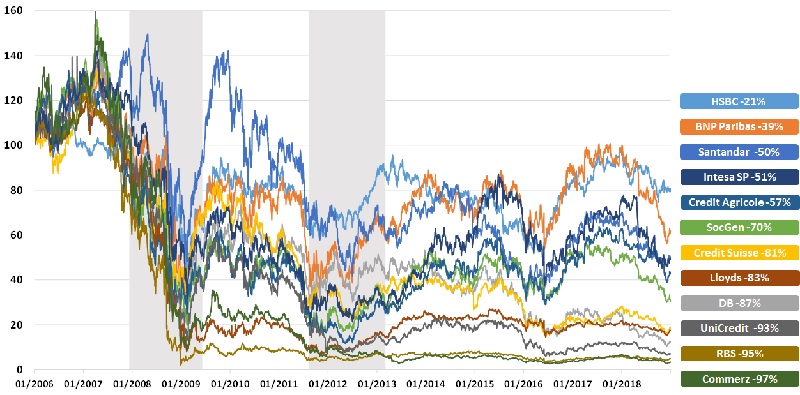

Select European Bank Equity Performance Since 2006. Index = 100

Brussels has pushed for more cross-border mergers to solidify the banking union. There are also banking heads, including François Villeroy de Galhau (France Central Bank) and Jean-Pier Mustier (CEO Unicredit) who have advocated looking outside state lines for banking tie-ups.

However, national regulators and other detractors (e.g. the Netherlands and New Hanseatic League) are unlikely to push for any large cross-border mergers in 2019 (or in any year for that matter) without having a common deposit insurance scheme in place.

In-country banking consolidation is another story. Many agree that at +1,800 institutions, Germany is overbanked. Leaders have tried to address this by pushing for consolidation amongst some of the public sector savings banks. Helmut Schleweis, head of Germany’s Savings Banks was spearheading a 4-way merger amongst Helaba / NordLB / DekaBank / LBBW to create a €700BN “Über-Ladensbanken” until discussions with Lower Saxony recently collapsed. Germany, which holds a 15% stake in Commerzbank, is also looking for solutions to mitigate ongoing problems at Deutsche Bank.

Or take Spain which is also seeking a local solution for the country’s 4th largest bank Bankia, in which the government still holds a 67% stake. Previous governments promised to privatize Bankia by Dec 2019, but since its rescue in 2012, the country has elected a fragmented government with different opinions on how to move forward. One of the main problem’s is Bankia’s share price trading around €3.00/share (vs. 2012 ~€1,400/share) posing a significant loss to taxpayers. It is unlikely that the government will move aggressively with the sale if the price doesn’t rebound by December. The left-leaning Podemos party wants to cancel the privatization entirely. Bankia’s current chairman reportedly wants to push on with the sale and has been working with PSOE to orchestrate a potential merger with Spain’s BBVA.

In 2019 and throughout the near term, investors in this space are likely to see governments and regulatory authorities attempting to sculpt national champions out of their smaller or regional troubled banks rather than see the creation of large cross border institutions that the ECB desires.

Activists Investors are Gaining More Support from Asset Managers to Deconsolidate European Conglomerates – when it makes sense

After a decade of monetary expansion, the amount of money floating in the system is unprecedented. Vanguard and Blackrock surpassed $5 trillion and $6 trillion respectively in assets under management last year. To put that into perspective, Blackrock and Vanguard are each managing sums equivalent to the nominal GDP of Japan, the 3rd largest nation in the world.

At that size, assets managers that were traditionally passive are becoming more proactive about all aspects pertaining to the companies that make up their portfolios in a concerted effort to 1) drive returns in a low yield environment and 2) sit alongside nation-states as giant “corporate-states” that are increasingly shaping policy. 2018 examples include:

- Railpen (£28BN AUM) wrote to more than 200 of its holding companies requesting enhanced disclosure with updated policy on board composition, remuneration, and shareholder rights;

- Norway’s council of ethics recommended that its sovereign wealth fund (+$1 Trillion AUM) divest 11 companies including BAE Systems, Fluor Corp, AECOM and Huntington Ingalls due to ethics violations;

- Denmark’s largest commercial pension fund PKA ($77BN AUM) divested 35 oil and gas companies citing environmental reasons. To date, PKA has eliminated 40 oil and gas and 70 coal companies, replacing them with climate companies;

- The Netherlands civil service pension fund ABP (+€400BN AUM) divested a number of tobacco and nuclear weapons companies

Last year, Blackrock urged CEOs to engage with activists who bring “valuable ideas” to the table. This is an importing shift in thinking which coincides with the current economic cycle which some interpret as cheap for European equities. The Stoxx Europe 600 12 month P/E ratio is below its 10-year average at ~12.5x while there were 131 campaigns across Europe as at Sept. 2018; this compares to just 6 campaigns in 2009.

The ongoing sagas at Telecom Italia, Bayer and ThyssenKrupp foreshadow what to expect from activists across the continent this year. Europe is replete with conglomerates and family-run businesses that were put together over previous centuries but are rooted in unpalatable governance structures. These conglomerates are now being targeted to sell or spin-off divisions. Siemens, for example, spun-off of its medical engineering division Healthineers last year, while activist campaigns at Barclays, Pernod Ricard are also underway.

PE funds, which are collectively sitting on +$1 trillion of dry powder, and Event Driven strategies, which enjoyed Q3-18 cumulative net inflows of ~$13BN, are both likely to benefit from the increased activity this side of the Atlantic.

Brent Oil is Caught between NOPEC and OPEC+

Energy prices made up nearly half of the ~2% HIPC inflation rate in Q3-2018 and serve as a crucial factor to watch as the ECB wavers on rate hikes. Brent, which is at ~$60/bbl but almost 25% below its October 2018 ~$80/bbl highs, is likely to see another volatile 2019.

The US, which overtook Russia and Saudi Arabia in 2018 to become the largest global oil producer, has leveraged its ongoing fracking boom in the Permian Basin of Texas to increase production to 11MM bbls/day (+1.6MM bbls/day vs. 2017). Today, the US is arguably on track to hit 15MM bbls/day in the next 5 – 10 years.

In an effort to appease voters, the Trump administration spent 2018 lobbying OPEC and others like Russia (or “OPEC+”, which controls >50% of the world’s oil supplies) to keep oil prices low by increasing output. Despite these lobbying efforts, OPEC+ decided to counter US appeals and cut production by 1.2MM bbl/day in December 2018.

Russia needed ~$50/bbl to balance its 2018 budget. This implies that it is under less pressure to scale back production any further. Saudi Arabia, which reportedly needs ~$70 – $75/bbl to balance 2019 budget, will continue to rely on its $350BN in reserves (down from $520BN in Jan 2015) to counter any budgetary pressures. As the US weaponizes sanctions, Russia may look to go beyond symbolic “high fives” with Saudi Arabia in 2019 and further curtail production in an effort to curry favor with Saudi Arabia’s MbS and retaliate against US sanctions. It’s against this backdrop that one might envisage Brent increasing further in 2019.

However, since the US lifted its oil export ban in 2015, American crude sales to Europe have exploded ~22x from ~6.5MM bbls/annum in 2015 to ~145MM bbls/annum by 2018. The Brent-WTI spread increased from an average of ~$3.30/barrel in 2017 to ~$4.50/barrel in 2018 underpinning the increased trading volume. Obviously, the US is eager to protect this trade flow.

Looming in the background (for now) is US antitrust NOPEC legislation which Trump has threatened to use against OPEC and sue for anti-trust violations in the coming months. As of this writing, NOPEC had been approved by the House, but still needed approval by the Senate. Senator Lindsey Graham, recent chairman-elect of the Senate Justice Committee, and Diane Feinstein, ranking Democrat on the committee, have voted for similar legislation in the past. And unlike Obama and Bush in prior administrations, Trump supports the proposal. If NOPEC is ratified and the US decides to then deploy it against OPEC, it could significantly weaken the cartel’s power potentially spurring more countries to follow Qatar out of the group.

Sanctions are a Credible Risk to Companies Involved the Europe’s Latest Natural Gas Pipeline

As a result of the Paris Agreements on Climate Change, the EU committed to phasing out its use of coal by 2030. Many of the 300 power plants splashed across the EU are coal-powered and, of the top 20 coal-fired power plants, 8 are located in Germany. Germany’s phase-out alone represents more than 21,000MW of capacity that needs to be replaced by 2030. Bottom line is Europe needs cheap gas.

So, Russia’s $11BN Nord Stream 2 pipeline project will be an important development to follow in 2019. Gazprom is nearing the completion of its pipeline which spans from Russia’s Ust-Luga region directly into Germany. The pipeline doubles Gazprom’s capacity to 110 bcm allowing it to deliver ~2 trillion cubic feet of gas annually.

Nord Stream 2 is contentious for two reasons. Firstly, it bypasses Ukraine and other Eastern European countries by redirecting transit gas away from those countries by using the Baltic Sea bed to reach Germany directly. This deprives those countries of transit fees; Ukraine estimates it would lose $3BN annually because of Nord Stream 2. The relationship between Ukraine and Russia imploded after the 2014 events in Crimea. The US had initially thrown its support behind Ukraine but this support may be waning under the current administration.

Secondly, the US argues that Nord Stream 2 makes Europe more reliant on Russia. Russia sent 195bcm of natural gas to Europe in 2017, increasing its market share to ~35%. Meanwhile, the US became a net natural gas exporter for the first time in 60 years in 2017. US LNG export capacity reached 3.6 Bcf/d last year, and with new LNG terminals coming online this year, US LNG export capacity is set to expand to 9.6 Bcf/d by year-end. Europe’s growing energy demand makes it an ideal market for the extra US supply as natural gas supplies from Europe dwindle and countries seek to become cleaner.

Trump has threatened to invoke CAATSA sanctions against parties involved in the pipeline’s construction, putting several companies in his crosshairs including Gazprom (Russia), Engie (France), OMV (Austria), Shell (UK/Netherlands), Uniper (Germany), Wintershall (Germany) and potentially Saipem (Italy) and Allseas (Switzerland). Despite these threats, Russia and Germany have reiterated that construction is unlikely to stop at this point.

Conclusion

So what is the conclusion? If it could be encapsulated in one sentence, it would be “Price in the unexpected”. The previous comments set a general overview of some of the key themes we consider fundamental when considering putting money to work in Europe this year.

Anthony Ugorji – CEO